Hidden environmental costs of the ‘fast fashion’ movement

August 3rd, 2017

Today’s fashion trends often come fast and cheap. Although we can now keep up with the latest moves in the industry at an affordable price, what about the hidden environmental costs of the ‘fast fashion’ movement?

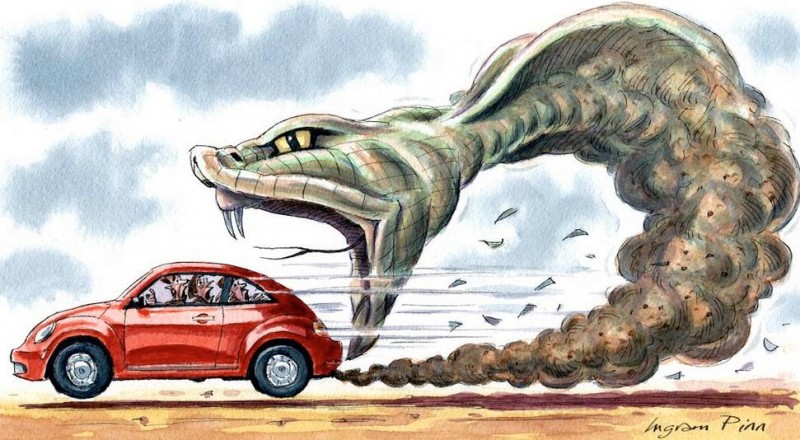

One such cost comes from the widespread use of viscose thread, a semi-synthetic fibre made using dissolved wood pulp, which is dyed and woven into the fabric.

The process dissolves pulp with intensive chemicals to produce a viscose solution (hence the name), which is then spun into fibre that goes on to become the clothing on our backs.

Viscose can be produced using a number of plants, but the main source for natural cellulose is wood pulp from the likes of Canada’s Boreal forests, the Amazon, and the ancient forests of Indonesia.

The delicate ecosystems of these forests, home to some of the most unique species on earth, are being devastated.

Corporate Responsibility

According to a recent Changing Markets report brands like Zara and H&M have been unknowingly sourcing their viscose fabrics from factories dumping toxic wastewater into local waterways, exposing marine life and local populations to harmful carcinogens.

According to a recent Changing Markets report brands like Zara and H&M have been unknowingly sourcing their viscose fabrics from factories dumping toxic wastewater into local waterways, exposing marine life and local populations to harmful carcinogens.

It is estimated that 120 million trees are logged every year to be turned into cellulosic fabric. And demand for cellulose is only on the rise, with dissolving pulp production expected to double by 2050.

Swedish behemoth H&M, for example, will have released 600 million items of clothing on the market in 2017 alone and is expanding its physical locations at 15 to 20 per cent per year.

Some members of the fashion community have come out of the closet on the issue such as pioneering brands like Stella McCartney with their Environmental Profit and Loss.

McCartney is working with the not-for-profit Canope to source sustainable viscose from certified forests in Sweden.

H&M is following suit with their sustainable capsule collection ‘H&M Conscious’ and the group’s sustainability report outlines plans to use 100 per cent recycled or otherwise sustainably sourced materials by 2030.

Inditex, which owns Zara, has followed suit with their ‘Join Life’ range and a corporate responsibility agenda.

However, is this really enough? Is the fashion industry just feeding us another line? And how can we, the consumer, shop conscientiously when brands don’t fully know the conditions in which their garments are made?

One simple and key solution is to buy less.

Less is More

As long as fashion cycles and fashion business models remain the same, corporate sustainability reports would appear to be simply greenwashing.

But thankfully fashions change, and so do opinions and preferences of shoppers.

A 2015 Nielson poll shows that 72 per cent of millennials are willing to pay more for environmentally sustainable products. So it seems someday in the future (when millennials take over) it will be fashionable to be fashion conscious.

But change isn’t happening fast enough to catch up with fast fashion. And what does sustainability actually mean?

You could say trees are renewable resources but then consider that it takes 30 years for a pine tree to grow.

As the Guardian pointed out in an article about Deforestation for Fashion, “a forest habitat is not as renewable as an individual tree may be”.

Likewise, pulpwood plantations have a major impact on the climate. Changes in land use, such as the techniques used to establish plantations, have helped make Indonesia of the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Alternative Options

Customers can help mitigate the issue somewhat by deciding where to shop and what to buy.

There are alternatives available like fibres from agricultural straw or recycled fabrics. EcoPlanet Bamboo, for example, is exploring ways of processing cellulose sourced from bamboo plantations grown on degraded lands. Likewise, viscose made from cotton linters can also provide an alternative to trees.

There are alternatives available like fibres from agricultural straw or recycled fabrics. EcoPlanet Bamboo, for example, is exploring ways of processing cellulose sourced from bamboo plantations grown on degraded lands. Likewise, viscose made from cotton linters can also provide an alternative to trees.

Tencel is a sustainable fabric, regenerated from wood cellulose. Produced in a closed looped system it uses less land and water that cotton production and 99 per cent of chemicals and solvents used in the process are recovered and recycled.

Ten major cellulose fibre producers produce 80 per cent of the world’s viscose fibre. If these producers respond to customer demand we will no longer have to wear clothing associated with deforestation, habitat and biodiversity loss, not to mention the threat to indigenous communities as they struggle to maintain rights to their lands.

Ultimately every choice we make comes at an environmental cost. Even when we keep it simple with a classic white shirt and blue jeans, and even if the cotton is organic, it still takes more than 5,000 gallons of water to manufacture a t-shirt and jeans.

Let’s say you shop exclusively second hand, even that comes at a cost. The East African Community, which comprises Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, and Rwanda have recently proposed banning all second-hand clothes and shoes because imports from the US and Europe are devastating local clothing industries.

So whatever the product, fashion usually involves long convoluted supply chains of production, textile manufacture, pattern cutting and clothing construction, shipping, retail, use and disposal of goods (Not forgetting the raw materials themselves, farming, harvesting, and processing etc).

The solution is to change our habits, consume consciously, and consume much less.

[x_author title=”About the Author”]