Is there a role for LNG in Ireland’s ‘fair share’ of global climate action?

October 22nd, 2019

If we are to hold global temperature rise to limit climate change impacts to “tolerable” or “adaptable” levels, the best current scientific understanding tells us that the total cumulative release of carbon dioxide must be capped.

Beyond that point, net emissions of CO2 must be zero. This finite amount of allowable further CO2 emissions is called the global CO2 budget (GCB). In recent work at DCU in collaboration with TCD, we attempted to assess the equitable share of the remaining global CO2 budget available for Ireland aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement – a so-called national CO2 quota (NCQ).

We arrived at a prudent, minimally equitable, Paris-aligned national quota of just under 400 MtCO2 from 2015. Climate action consistent with this quota would require the realisation of cumulative net-zero CO2 emissions from 2025 onwards.

This may be contrasted with even the most ambitious mitigation action envisaged in the 2019 Irish Climate Action Plan which targets net-zero emissions no earlier than 2050.

The large discrepancy between these measures of the urgency of climate action may be accounted for by a combination of procrastination, hardening of scientific understanding of the risks of higher temperature rise, an inadequate allowance to date for the equity dimensions of action, and tacit reliance on future deployment of speculative “negative emissions technologies”.

While there is scope for some limited debate over the severity of the challenge, it is clear that relatively wealthy nations with high per-capita CO2 emissions must achieve net-zero annual CO2 emissions much earlier than 2050 if the temperature and equity objectives of the Paris Agreement are to be respected.

A bridge to nowhere

Natural gas currently plays a central role in the Irish energy system and is regularly asserted to be a fuel with a significantly lower CO2 emission intensity than other fossil fuels that can function as a “bridge” or “transitional” fuel in overall energy system decarbonisation.

In the case of Ireland, it has been argued that, even under plans for deep decarbonisation, natural gas can and should continue to be used at a significant scale until at least 2050 and perhaps beyond.

Then, even with the most rapid possible roll-out of wind and solar, it is argued that natural gas will still be “essential” as the fuel of last resort to cover periods when those intermittent sources are not available.

It is suggested that, if necessary, emissions from natural gas can be adequately addressed by “carbon capture and storage” (CCS) systems where CO2 is captured during combustion and stored deep underground.

However, there are two key difficulties with this approach. First, it assumes a relatively late net-zero date of 2050 or beyond. If net-zero must be achieved much earlier, then the window for a temporary transition to a somewhat lower emissions intensity fossil fuel becomes much shorter, and the case for investment in shorter-lifetime infrastructure becomes correspondingly weaker.

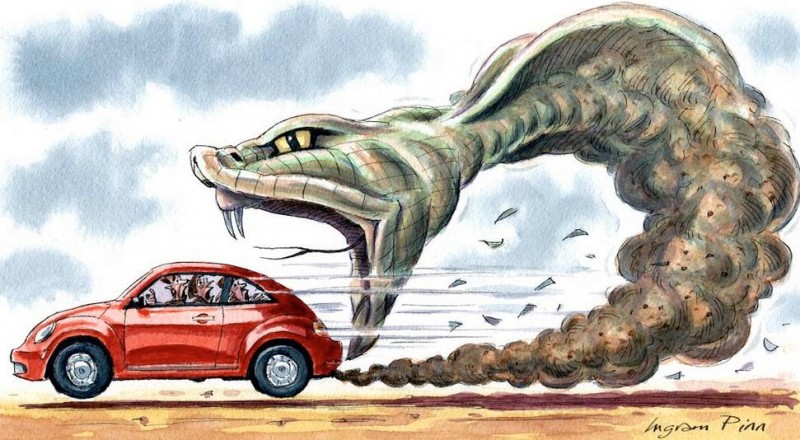

Second, the assessment of lower CO2 emissions intensity is strictly correct only at the point of combustion. If “upstream” emissions in extraction, processing, and transport are accounted for, then the case is much more complex to assess.

As fugitive upstream releases of methane – itself a very potent greenhouse gas – are a specific attribute of natural gas use, the substitution of other fossil fuels by natural gas does not necessarily yield nearly the degree of climate mitigation that is claimed on the narrow basis of combustion emissions. Further, carbon capture and storage does nothing to mitigate upstream emissions.

As to the argument that natural gas is required for reliable electricity generation, there are in fact multiple alternatives. In the Irish case, a combination of hydroelectricity, interconnection, bioenergy (with high sustainability criteria) and power to hydrogen use for large scale energy storage can address most if not all requirements and at feasible costs.

LNG problematic

The general case for natural gas as a transitional, lower intensity, fossil fuel is thus problematic in itself. But in the specific case of liquefied natural gas (LNG), it is further undermined by two additional factors.

First, liquefaction and liquefied transport are energy-intensive processes that require continuous refrigeration to −162°C. This has the double-headed problem of reducing net energy yield and increasing emissions intensity compared to conventional purely gaseous supply chains.

Second, it is widely understood that the primary source of LNG imported to Ireland is likely to be gas extracted by way of hydraulic fracturing or fracking. While it is difficult to be precise, there are indications that such extraction may be significantly more vulnerable to methane release than conventional extraction.

Again, it must be emphasised that such upstream emissions cannot be mitigated in any way by downstream interventions such as carbon capture and storage. In relation to energy security, the first overriding requirement is to secure a liveable environment through commensurate climate action that a natural gas “bridge” simply cannot deliver.

In addition, the best way to address security of supply is by maximising the use of indigenous, very low emissions energy sources. Ireland is almost uniquely placed for such an energy security strategy to be cost-effective based primarily on onshore and offshore wind combined with very large scale energy storage via power-to-hydrogen and related technologies.

As with all industrialised countries, Ireland now faces an acute challenge in rapidly decarbonising its energy system, the scale, and urgency of which is not yet widely appreciated. There are no simple or easy solutions.

It is clear, however, that the deployment and potential lock-in of additional fossil fuel infrastructure is more likely to hinder, rather than help, in mounting an effective response.

By Professor Barry McMullin

Prof McMullin is a lecturer in the Faculty of Engineering and Computing in Dublin City University and is also a member of An Taisce’s climate committee.