What’s the deal with methane?

25 August 2021

The IPCC report released a few weeks ago stated that strong, rapid and sustained reductions in methane emissions are needed to limit further warming.

Even though methane is one of the most powerful greenhouse gases, it can also be a bit misunderstood. Most of us know that it has something to do with cow belches and that is a more powerful warming force than carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. But that still leaves a lot more to uncover.

To extract out what’s important to know, we talked to some people in the know to give you the low-down on methane.

Let’s start with the basics. What is methane?

The lesser-known greenhouse gas has been referred to as the ‘climate’s low hanging invisible fruit’ and as a ‘live-fast die-young’ greenhouse gas.

Methane (CH4) has a global warming potential 28 times that of carbon dioxide emissions over a 100-year period – it ‘lives-fast’. It is a ‘die-young’ greenhouse gas because it stays in the atmosphere about 12 years, after which it breaks down into carbon dioxide and water.

This is “a very potent, powerful, greenhouse gas,” according to climate scientist and research fellow Paul Price. But he also said, “it can be confusing to say it’s a short-lived gas.”

If we continue emitting the gas, then the warming effect will continue as well. This is despite methane’s shorter atmospheric lifespan than carbon dioxide’s – a gas with a lifespan that is “essentially forever”, according to Mr. Price.

Mr. Price uses a helpfulanalogy of a tap:if the tap is on, and we are emitting the gas, there will be a continued warming effect. But if the flow (i.e. annual emissions) decreases, then the warming will decrease.

So, the short-lived nature of the gas is only beneficial to mitigate the effects of climate change if we actually reduce emissions.

Alright, I get methane’s impact in the atmosphere, but where does it come from?

Methane comes primarily from three sources – fossil fuels, waste, and agriculture.

It leaks during oil and gas extraction as well as throughout the production of coal. Globally, those fossil-fuel related activities account for 35 per cent of methane emissions. Landfills and waste management account for a further 20 per cent of emissions and agriculture accounts for the remaining 40 per cent of the methane pie. (Livestock is the largest source of methane within agriculture, but more on that later).

There are anthropogenic (read: human-caused) sources of methane and there are natural sources of methane. The difference between the two is related to agency.

As Mr. Price stressed, “If we can make choices that can reduce it and mitigate it, then that is a reduction in anthropogenic greenhouse forcing.”

Many of these sources would leak methane regardless of human activity. For example, coal in the ground is natural source of methane. But when humans intervene and extract that coal at an accelerated rate, it becomes anthropogenic.

I’m guessing the methane source that is most relevant in Ireland is agriculture – is that right?

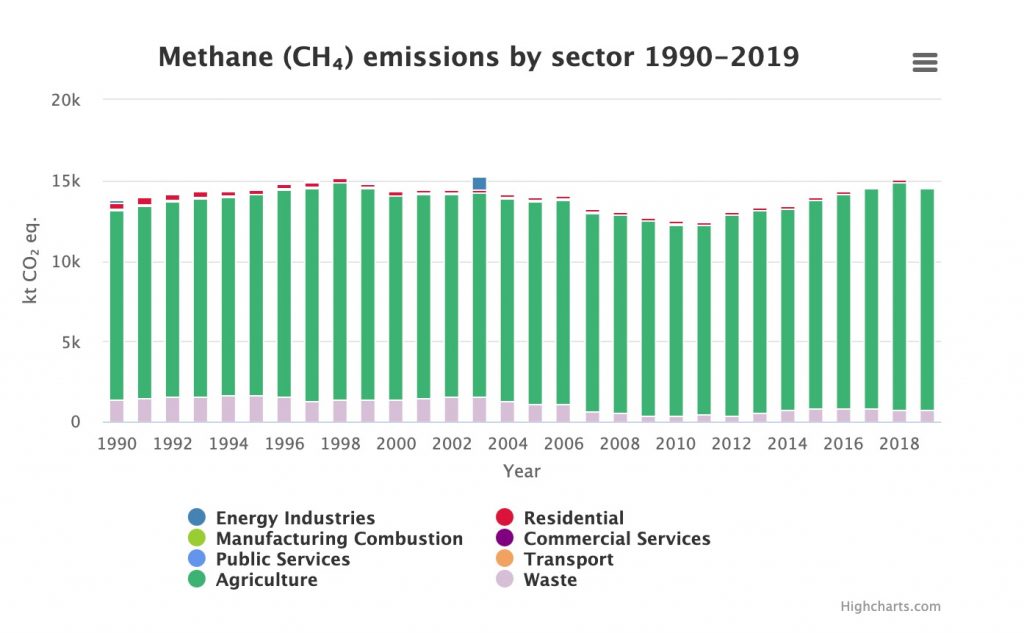

Bingo. Agriculture accounts for just over one third of Ireland’s total greenhouse gas emissions and over 93 per cent of total national methane emissions.

In agriculture, methane comes mainly from cows. In Ireland, cattle account for 85 per cent of agricultural methane – and 77 per cent of total national methane emissions.

Environmental scientist and farmer Emma Carroll recognises that methane is “one of the biggest problems in Ireland, in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.”

She stressed that farmers face both the pressure to produce food and the pressure to reduce emissions.

“We can do better,” she told The Green News.

What are some ways the agriculture sector could reduce their methane emissions?

There is a certain amount of methane emissions that are locked in as long as cattle are raised in Ireland. But we do have some agency in this – both in terms of herd size, and in how livestock waste is managed.

“There are other technologies that we could possibly use that would be really helpful. Both from a farming perspective and also from a greenhouse gas perspective,” Mrs. Carroll said.

One potential technology to look at is anaerobic digestion. This process (which could probably have its own explainer) uses the absence of oxygen to break down animal waste. The result is methane-rich biogas which produces heat, and can be used to generate electricity.

But anaerobic digestion can “create a positive feedback effect to create more emissions and more nitrogen use,” according to Mr. Price.

He says that this process makes some “bad assumptions”, and noted the concerns that he and others have. For example, creating a higher demand for animal waste could lead to an increased demand for bigger herds, which leads to more emissions. There is a similar unintended consequence with nitrogen use – more demand of the output can also lead to more demand on the input.

Most of the methane emissions comes from the cow’s digestions, so diet modifications are another way methane could be reduced. Mrs. Carroll says, people suggest feeding the cows seaweed, but she says “it’s not really that simple.”

There are other things to consider, like how much seaweed would need to be grown, and if it would affect marine ecosystems. Recent reports also indicate that the amount of methane reductions the feed would bring would also be relatively low.

(Want to read up more on that? Wired had a piece on it earlier this year).

Then, there are the anthropogenic sources of methane. When milk quotas were abolished, it led to an increase in Ireland’s livestock herd and dairy cow numbers increased by one third from 2010-2018.

“We have control over how many cows there are and what kind of cows they are,” said Mr. Price. He stressed that dairy cows emit more methane than other cows.

Considering the type and amount of livestock, he says we can take responsibility for what we do control and can work to emit less.

I’ve heard some talk about ‘biogenic methane.’ Is that methane any different than regular methane?

Yes, and no.

Biogenic methane is methane that comes from living creatures – that’s where the bio comes in. it comes from biological processes rather than other processes like leaking methane gas from coal. It breaks down slightly differently than other kinds of methane. But it doesn’t make that much of a difference.

“When you’re talking about biogenic, it’s being used as if that means natural, but it isn’t natural,” according to Mr. Price. He stressed that methane has the same warming effects, regardless of the source.

“Methane with a fossil carbon atom in it has the same effects until it breaks down as one with a biogenic carbon atom in it,” he told The Green News.

Mrs. Carroll echoed this point. “Methane is methane in the atmosphere. The atmosphere doesn’t discriminate.”

Does it seem likely that we will reduce methane emissions in Ireland?

It largely depends on how the agriculture sector responds.

With the EPA calling for greater cuts to meet targets and scientists still working to emphasise the importance of methane, it seems that agriculture has yet to step up and reduce their emissions.

As a farmer, Mrs. Carroll acknowledges the challenges that face this sector. Farms are Ireland’s most dangerous work places. Speaking from her experience, she says that “farmers are just out there doing their bloody best. It’s hard, it’s really, really hard.”

With demands to increase production and balance their books, it can be challenging for farms to fund ways to reduce emissions. So it’s a difficult system. But she believes it’s possible for farmers to get on board, especially if it secures their future.

“We can make these changes,” Mrs. Carroll urged. “We need leadership to step up. We need communication to improve, but I’m hopeful and I’m optimistic that we can do it.”

By Sam Starkey

Correction: an earlier version of this article cited “cow farts” rather than “cow belches.” It also used a Teagasc article for methane emissions, which included nitrogen in agricultural emissions. This version attributes methane stats to the EPA, with data from 2019. Quotes from Mr. Price have been edited for clarity.