Opinion: the intersections between the housing and climate crises cannot be overlooked

4 February 2022

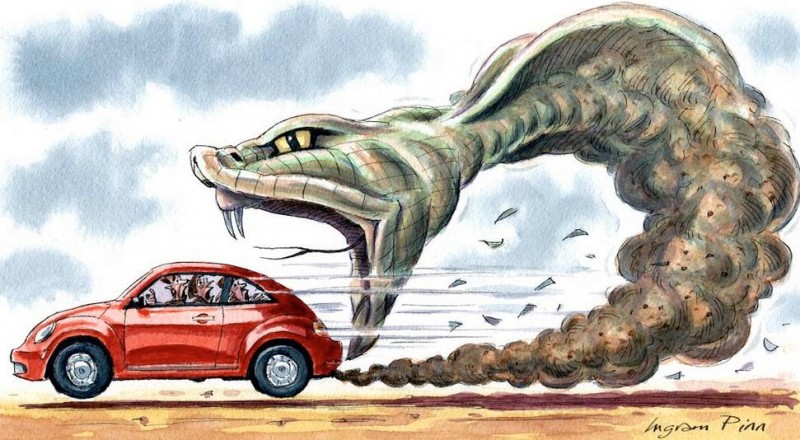

You often hear climate change described as an opportunity – but that approach is a technocratic myth. It hinges on electric vehicles, blanket carbon taxes, and seeing natural gas as a bridging fuel – all of which maintains the status quo when it comes to the way we live our lives.

And it does nothing to address the systemic inequalities experienced by those most at risk to the impacts of climate change.

The poorer and disadvantaged within our communities will continue to struggle to afford adapting to the environmental crisis. They will face increased costs due to less efficient housing insulation, more carbon intensive home-heating fuels and not being able to switch their car to electric.

The intersectionality of the climate crisis and minority communities cannot continue to be overlooked. For decades, communities the world-over that are not white nor wealthy face higher levels of water contamination and air pollution. These communities are the most vulnerable to heat stress and the least adaptable to drought and food losses.

When climate solutions are discussed in Ireland, they often exist in a binary system. We must bring a holistic attitude to them, and we can do so with housing.

In 2020, residential emissions accounted for 12.3 per cent of Ireland’s emissions makeupand that number needs to come down in order to meet national targets. duction in these emissions is critical to ensure Ireland reaches our carbon output reduction targets.

As it stands, low-income earners in Ireland are more likely to use coal and peat to heat their homes. These households are those who are greatest affected by carbon taxes on household fuels. They already can’t afford to retrofit their homes. They can’t afford photovoltaic cells. They can barely afford the fuel they’re currently using.

This regressive model of carbon taxing ensures people cannot afford to easily switch to lower emission alternatives such a heat-pumps. The strategy of costing them out is therefore illogical and inequitable.

There’s also the fact that people who live in apartments have little to no say in the types of insulation used in their building and that occupants of council houses are often subject to the living conditions that are in place when moving in.

Affordability and lack of options ensure that people who don’t own and/or cannot afford to buy homes are stuck with the situation before them. Rented properties are therefore typically less energy efficient than owner-occupied homes, just ask any student. (Any student can tell you that.)

In Ireland, up to half of households owned by local authorities fall below a D energy rating.[3] 60 per cent of the occupants of these are unemployed or retired, meaning they lack the disposable income to further improve the quality of their home.

Those renting are understandably hesitant to invest in infrastructure when they are unsure if they will remain long enough for it to be economically worthwhile for them.

The latest Climate Action Plan sets out an objective to retrofit 500,000 homes over the next decade. They also include a commitment to install 400,000 heat pumps, leading to a 33 per cent reduction in residential emissions. But ultimately, this plan falls critically short of reaching the climate targets needed to curb our emissions.

So, what are some of the solutions?

Firstly, environmental regulations must be part and parcel of every single construction project. The government must mandate that new builds follow a prescribed number of positive environmental practices. This would include more sustainable low carbon building materials being used but may also manifest as a number of PV cells per area of roof, no indoor fires or stoves, no gas or oil boiler infrastructure, heat pumps, and triple glazed windows, as standard.

Secondly, county councils must be properly funded to adequately construct A1 rated homes for all those in need and to retrofit those already in possession. The people who require these homes are already some of the most vulnerable in society. This way, we can address our environmental peril and alleviate some of the injustices people face.

Thirdly, people need a low/no cost loan option to afford to retrofit and upgrade their homes. The state should provide funds for homeowners to carry out the work done. These could be borrowed at low cost from the ECB and should be looked at as an investment into future populations – into their health, their community, their labour.

Another alternative would be to establish a housing and retrofit agency to carry out this work by the state. With only 1200 local authority houses refurbished in 2020, it would take until the new century to achieve our goals. As we know, even 2030 is too late for some.

Lastly, we need to completely de-commodify housing. Houses are not an asset to be bought and traded. They are a necessity of one’s being. They are not just a physical structure but provide a structure for one to base their life around. Housing is a fundamental human right. However, that is not recognised by Irish Law. We have an opportunity to link these inseparable facets of life together in law.

Energy poverty and homelessness cannot exist in a Just Transition. The state must ensure that before proclaiming any sense of accomplishment in housing delivered or addressing climate change.

By Criodán Ó Murchú