A gallery of extinct Irish animals from St Patrick’s time

[cs_section id=”” class=” ” style=”margin: 0px; padding: 45px 0px; ” visibility=”” parallax=”false”][cs_row id=”” class=” ” style=”margin: 0px auto; padding: 0px; ” visibility=”” inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=””][cs_column id=”” class=”” style=”padding: 0px; ” bg_color=”” fade=”false” fade_animation=”in” fade_animation_offset=”45px” fade_duration=”750″ type=”1/1″][cs_text id=”” class=”” style=”” text_align=””]March 15th 2016

To commemorate St Patrick’s day we have created a compilation of mammals that have become extinct in Ireland since the fifth century when St Patrick was still alive. Quite a few of these animals disappeared from Ireland hundreds of years ago, while others only died out recently. Some of the species mentioned are still alive today in other parts of Europe and the world, but others have become completely extinct from this world. All the animals in list have become extinct in Ireland due to human activity. Hopefully analyzing how these animals became extinct can be used to preserve wildlife that currently inhabit Ireland, Europe and the world.[/cs_text][/cs_column][/cs_row][/cs_section][cs_section id=”” class=” ” style=”margin: 0px; padding: 45px 0px; ” visibility=”” parallax=”false”][cs_row id=”” class=” ” style=”margin: 0px auto; padding: 0px; ” visibility=”” inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=””][cs_column id=”” class=”” style=”padding: 0px; ” bg_color=”” fade=”false” fade_animation=”in” fade_animation_offset=”45px” fade_duration=”750″ type=”1/1″][x_slider animation=”slide” slide_time=”7000″ slide_speed=”1000″ slideshow=”false” random=”false” control_nav=”false” prev_next_nav=”true” no_container=”false” ][x_slide]

The gray wolf or grey wolf (Canis lupus), also known as the timber wolf or western wolf, is a canid native still alive in the wilderness and remote areas of North America and Eurasia. It is the largest extant member of its family, with males averaging 43–45 kg (95–99 lb), and females 36–38.5 kg (79–85 lb). Like the red wolf, it is distinguished from other Canis species by its larger size and less pointed features, particularly on the ears and muzzle. Its winter fur is long and bushy, and predominantly a mottled gray in color, although nearly pure white, red, or brown to black also occur.[/x_slide][x_slide]

The wolf itself was once one of the most common land based mammals on the planet, and existed in the whole of the Northern hemisphere and on the Indian subcontinent. Sub species also existed in parts of Africa and South America. As human populations across Europe grew the wolf population suffered. There were many reasons for this, loss of habitat and decline of prey certainly contributed but a building hatred toward the species, mostly based on myth and folklore, resulted in their removal from large parts of Western Europe, with only isolated populations remaining.

The grey wolf, Canis lupis, was once reasonably common in Ireland and existed on all parts of the Island. The last wolf in Ireland was probably killed in or around 1786 but small populations or individual wolves may have existed into the early 1800’s. Before English rule in the country wolves were hunted, mainly by the ruling classes, and plenty of wolf skins were exported to Britain, but there seems to have been no coordinated attempt to exterminate them. During English rule this changed, and people began to view wolves as a troublesome species and targeted them for extermination. During Cromwell’s rule bounties for wolves were initiated and so began the complete removal of the wolf from the Irish landscape.[/x_slide][x_slide]

The European wildcat (Felis silvestris silvestris) is a subspecies of the wildcat that inhabits European forests, as well as forested areas in Turkey and the Caucasus Mountains.

The European wildcat is much bigger and stouter than the domesticated cat, has longer fur and a shorter non-tapering bushy tail. It has a striped fur and a dark dorsal band.[/x_slide][x_slide]

Deforestation, the pollution of natural resources and the increasing numbers of people and the size of towns and cities after the Middle Ages led to the extinction of the Wildcat in Ireland some time before the 19th century.

Wildcats were still hunted for their fur and also became classed as vermin accused of annihilating stocks of lamb, game birds and chickens as part of an anti-wildcat propaganda campaign that still lurks today.[/x_slide][x_slide]

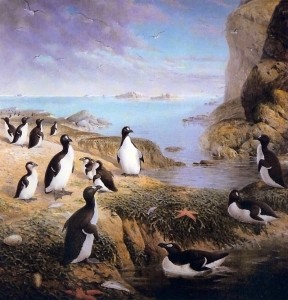

The great auk (Pinguinus impennis) was a flightless bird of the alcid family that became extinct in the mid-19th century. It bred on rocky, isolated islands with easy access to the ocean and a plentiful food supply, a rarity in nature that provided only a few breeding sites for the auks. When not breeding, the auks spent their time foraging in the waters of the North Atlantic, ranging as far south as northern Spain and also around the coast of Canada, Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, Ireland, and Great Britain.[/x_slide][x_slide]

The Little Ice Age may have reduced the population of the great auk by exposing more of their breeding islands to predation by polar bears, but massive exploitation for their down drastically reduced the population. By the mid-16th century, the nesting colonies along the European side of the Atlantic were nearly all eliminated by humans killing this bird for its down, which was used to make pillows.

With its increasing rarity, specimens of the great auk and its eggs became collectible and highly prized by rich Europeans, and the loss of a large number of its eggs to collection contributed to the demise of the species.

The last colony of great auks lived on Geirfuglasker (the “Great Auk Rock”) off Iceland. When the colony was initially discovered in 1835, nearly fifty birds were present. Museums, desiring the skins of the auk for preservation and display, quickly began collecting birds from the colony. The last pair, found incubating an egg, was killed there on 3 July 1844, on request from a merchant who wanted specimens, with Jón Brandsson and Sigurður Ísleifsson strangling the adults and Ketill Ketilsson smashing the egg with his boot.[/x_slide][x_slide]

The Eurasian beaver or European beaver (Castor fiber) are one of the largest living species of rodent and are the largest rodent native to Eurasia. They weigh around 11–30 kg (24–66 lb), with an average of 18 kg (40 lb). Typically, the head-and-body length is 80–100 cm (31–39 in) and the tail length is 25–50 cm (9.8–19.7 in).[/x_slide][x_slide]

These animals became extinct in Ireland and other countries due to human persecution and anthropogenic habitat loss. Humans hunted these species for their fur and for castoreum a secretion of its scent gland believed to have medicinal properties. In medieval times, castoreum was used as treatment for headaches.

In many European nations, the beaver went extinct but reintroduction and protection has led to gradual recovery to approximately 639,000 individuals by 2003.[/x_slide][x_slide]

The gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) is a baleen whale that migrates between feeding and breeding grounds yearly. The grey whale is a medium to large (11-15 m) dark to light grey coloured baleen whale. The skin is mottles and these whales are often covered with patched of barnacles and crustaceans. This species lack a dorsal fin, but has a prominent dorsal hump followed by a series of 6-12 knuckles along the dorsal ridge. The females of this species tend to be larger than the males. The short baleen plates are coloured cream to pale yellow. The throat is allowed to extend during feeding by two to four throat grooves.[/x_slide][x_slide]

The grey whale has been extinct off our coasts since the 17th century, the time of Shakespeare’s Macbeth and the Battle of Kinsale. Subfossil remains of gray whales have been found in the Atlantic, and radiocarbon dating have shown the latest to have been from approximately 1674 AD. The Atlantic population was most likely hunted to extinction. Circumstantial evidence indicates whaling could have contributed to this population’s decline, as the increase in whaling activity in the 17th century coincided with the population’s disappearance[/x_slide][/x_slider][/cs_column][/cs_row][/cs_section]