Biofuels are worse than fossil fuels, research finds

27th April, 2016

The use of biodiesel for transport was meant to drastically decrease CO2 levels however instead it’s set to increase Europe’s overall transport emissions by nearly 4%, according to new research.

from the European Commission’s recent study on biofuels. Biomass is often described as a clean, renewable fuel and a greener alternative to coal and other fossil fuels for producing electricity. Buta European Commission study on biofuels has shown that many forms of biomass especially from forests produce higher carbon emissions compared to fossil fuels.

In particular, a growing body of peer-reviewed, scientific studies shows that burning wood from whole trees in power plants to produce electricity can increase carbon emissions relative to fossil fuels for many decades—anywhere from 35 to 100 years. This time period is significant: climate policy imperatives require dramatic short-term reductions in greenhouse gases, and these emissions will persist in the atmosphere well past the time when significant reductions are needed.

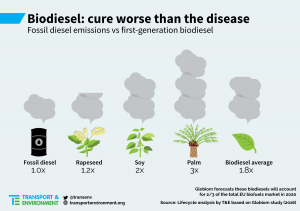

A new EU study found that palm, rapeseed and soy-based biodiesel to have land-use change emissions which happens when new or existing cropland is used for biofuel feedstock production that alone exceed the full lifecycle emissions of fossil diesel. The study analyses how on average, biodiesel from virgin vegetable oil results in around 80% higher emissions than the fossil diesel it replaces. For example, soy and palm-based biodiesel are even two and three times worse respectively. This type of biodiesel is the most popular biofuel in the European market and it’s predicted to have nearly 70% share in 2020. Overall more than three-quarters of biofuels, which includes bioethanol as well as biodiesel, are predicted to have lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions similar or higher than fossil petrol and diesel in 2020.

Executive Director of Transport and Environment Jos Dings stated that: “The cure is plainly worse than the disease. The 7% cap on food-based biofuels has helped though, and should be lowered to zero after 2020. These fuels should also not count as zero-emission fuels. If we do not end incentives for bad biofuels, the better ones will not stand a chance.”

There are also other potential consequences of using bioenergy which are equally detrimental. Based on the false assumption that all burning of biomass would not add carbon to the air, several reports have suggested that bioenergy could or should provide 20% to 50% of the world’s energy needs in coming decades. Doing so would require doubling or tripling the total amount of plant material currently harvested from the planet’s land. Such an increase in harvested material would compete with other needs, such as providing food for a growing population, and would place enormous pressures on the Earth’s land-based ecosystems. Indeed, current harvests, while immensely valuable for human well-being, have already caused enormous loss of habitat by affecting perhaps 75% of the world’s ice- and desert free land, depleting water supplies, and releasing large quantities of carbon into the air.

Last year the EU implemented reforms to decrease the use of land-based biofuels, however the reforms did not include indirect land-use change (ILUC) emissions, in the carbon accounting of biofuels under the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) and Fuel Quality Directive. This means that harmful biofuels can still be viewed by the EU as a target that would receive public financial support. The European Commission is currently reviewing the RED and sustainability criteria for all bioenergy including biofuels, and it will publish a proposal in the final quarter of this year.

[x_author title=”About the Author”]