COP25: Name and shame those holding the world to ransom

December 16th, 2019

And so after two weeks of negotiations, COP25 finally came to a fractious end last night, some 40 hours past the scheduled close.

As the remaining bleary-eyed delegates gathered for the final plenary, the stands were being dismantled, the protesters had departed and the motto of the meeting – Time for Action – had a hollow ring to it.

Make no mistake – this was a failure of epic proportions.

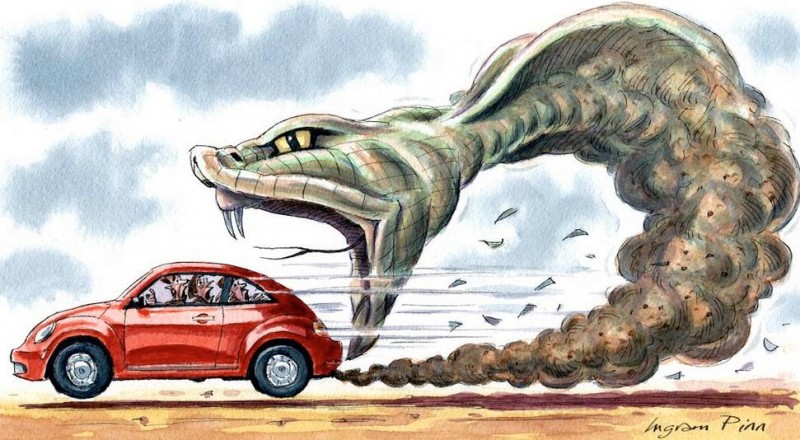

Whereas four years ago in Paris the countries of the world came together to do business, many only came to Madrid this month to obstruct progress and place narrow national and financial interests ahead of the urgent needs of the global community.

The science that told them there was less than a decade of present carbon budget left to burn to have a reasonable chance of avoiding the climate tipping points did not sway them.

Neither did the vigorous participation of the global youth and indigenous movements, nor the urgings of the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres who expressed his disappointment with the outcome. In his view, the international community had lost an important opportunity to show increased ambition on mitigation, adaptation, and finance to tackle the climate crisis.

Dangers of double counting

The main objective of COP25 was to finalise the remaining rules under which the Paris Agreement would be administered. Most of the non-contentious aspects were agreed upon in earlier meetings.

The chief concern at Madrid, however, was how the global trading of carbon would be implemented and how countries would be rewarded for safeguarding their carbon sinks, especially forests in areas such as the Amazon.

There was also the issue of whether unused carbon credits carried over from previous agreements would be recognised as part of any new trading regime. In these areas, it was the big emitting countries of the USA, Australia, and Brazil who sought to thwart the wishes of the smaller and more climate-vulnerable countries.

It was hoped that any agreed arrangements would not facilitate large increases in global emissions from these big countries that they could then offset against their credits. For some of the large emitting countries, however, this COP was clearly all about exploiting loopholes that might even enable them to double count their forest credits.

The stalemate that resulted pitched the US, China, Australia and Brazil against a coalition of smaller states and the EU. No resolution was obtained after two weeks of bitter wrangling. The issue was left unresolved and pushed back until COP26 in Glasgow next year – another year lost as global emissions continue to climb.

It is clear that many countries are not keeping to the pledges to contain emissions that they made in Paris, with a further round of stricter pledges due to be made by the end of next year. Some of the biggest emitters have questioned whether they would comply with this requirement.

Abandoning those on climate front line

Perhaps the only positive outcome of the meeting was the decision that new pledges will be delivered by this time next year. However, the enthusiasm for this came from around 80 countries, mostly small developing countries that account for only 10 per cent of global emissions.

The US will have exited from the Paris agreement altogether by this time next year and will not have to make any commitments at all. But this did not stop it from being obstructive, in particular when discussions concerned financial support for poor countries on the climate front lines.

Loss and Damage discussions have historically been uncomfortable topics for the US in particular given its historically high contribution to the present emissions problem.

Rising sea level, severe droughts and floods and unprecedented storms are affecting many poorer tropical countries that have no significant emissions profiles yet bear the brunt of climate impacts.

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change recognises this in its principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities. It was hoped this would be addressed in Madrid by an appropriate funds transfer arrangement but, once again, the big developed countries baulked at the prospect.

Self-interest: the calling card of COP25

Among the big power blocs, the EU (minus Poland) emerged with some credit as it unveiled its plan for carbon neutrality by 2050. But the EU only accounts now for 10 per cent of global emissions and needs active partners such as China, India, and the USA if the curve of increasing global emissions is to be turned downwards.

Ireland also needs to actively support EU ambition in a way that has not characterised its actions in former years. The recently unveiled Climate Action Plan is wholly deficient in contributing appropriately to emission reductions of 7.6 per cent every year for the next decade. We cannot criticise other nations for playing the national self-interest card if we ourselves seek to do the same.

There is no doubt but that the failure of COP25 is symptomatic of a world failing to advance the multilateralism ideals many of us grew up on. International cooperation in solving economics, politics and environmental problems such as ozone depletion have now given way to narrow national and populist ideologies.

What is most worrying about climate change is the disconnection between the power brokers and society at large. The advice of the scientists and the pleas of the young were ignored in Madrid.

Indeed some 200 young and indigenous people were summarily ejected from the conference after a protest. The eloquent arguments presented by young Irish activists at side events fell on deaf ears.

Attempts by some world leaders and some media commentators to direct personal vitriol against young activists even surfaced. In the words of Greta Thunberg:

“As you may have noticed, the haters are as active as ever — going after me, my looks, my clothes, my behaviour, and my differences…..It seems they will cross every possible line to avert the focus since they are so desperate not to talk about the climate and ecological crisis. Being different is not an illness and the current, best available science is not opinions — it’s facts.”

The denial of facts and the unwillingness to address the urgency of climate change as expressed so clearly by different segments of society and the supremacy of national self-interest over the needs of Our Common Home will, unfortunately, be the abiding memories of COP25.

By Professor John Sweeney

John is emeritus professor of geography, Maynooth University and has taught and researched various aspects of climate change for over 35 years.