COP25: Time to make a dent in rising emissions curve

December 8th, 2019

The annual Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change rotates around the continents to minimise travel and thus the carbon footprint involved and was this year due to be held in the Chilean capital of Santiago.

However, after a period of major civil unrest, the President of Chile declared a state of emergency and announced that Chile would be unable to host COP25. That unrest has continued over the past 50 days and now rates as the worst in the three decades since the end of the Pinochet dictatorship.

Though little reported in Irish media, it has led to over 25 deaths, more than 12,000 injuries and 20,600 people arrested. As a consequence of these unfolding events, the location for COP25 was switched at short notice to Madrid. This was the second relocation since the meeting was originally scheduled to take place in Brazil before the invitation was withdrawn by President Bolsonaro.

In any event, some 200 countries and 25,000 participants have now converged on a huge exhibition arena close to the airport in Madrid. The main purpose of the conference this year is to complete the finalisation of the rulebook for the Paris Agreement which comes into force on 1st January.

Though many of the details were agreed last year at COP24 in Poland, fractious negotiations then failed to satisfy some countries, especially Brazil, on how far carbon credits for forestry would be permitted as offsets for greenhouse gas emissions.

This has continued to provide an obstacle to progress here in Madrid over the first week of the meeting, not least as countries such as Brazil, India and China want to be able to carry over a huge number of unused credits gained in former years under the Kyoto Protocol.

This would allow them continued large scale increases emissions and severely compromise the achievement of the Paris objective of limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. At this stage, there is a real risk that ‘creative accounting’ will allow double counting of emission reductions to enable a compromise of sorts to be achieved.

Crucial days ahead

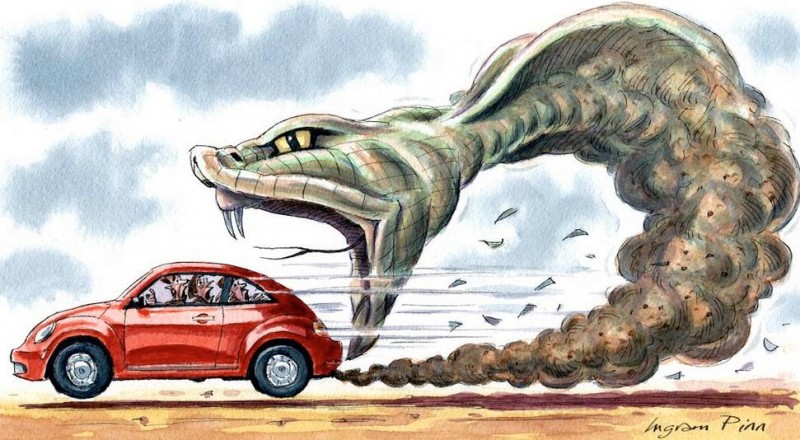

The next few days will be crucial in seeking to prevent this. Indeed the focus on the carbon market has increasingly turned the COP into a commercial ‘circus’ and taken the focus off where it should be – major reductions in emissions.

One might be forgiven for thinking that the global manifestation of concern for where we are headed in the climate change emergency would have encouraged negotiators to forgo national self interest in favour of what Pope Francis calls ‘Our Common Home’.

The global schools’ climate strikes, the sensitisation activities of Extinction Rebellion, the recent successes gained by environmental NGOs, not least in Ireland, have brought the climate emergency to the forefront of the political agenda.

But there is little evidence thus far of this occurring in Madrid. The arrival of Greta Thunberg and a strong representation of young people from around the world following in her footsteps has done little to soften the ‘hard bitten’ negotiators who beaver away behind closed doors with little external interaction with the rest of the participants. Their priorities are not global priorities. Rather it is ‘what’s good for my country first and foremost’.

This is not a recent phenomenon and it is simplistic to ascribe a narrow nationalistic focus to the rise of populism and demagogic leaders. Rather the roots run deeper into how political systems protect self-interest and vested interests and employ public servants to resist compromises even where they are in the long-term benefit of their populations.

So, it is not surprising that several countries here in Madrid are currently seeking to stall climate action where it suits them to do so. For some, this currently involves weakening any references to human rights in the rule book. Where these complicate exploitations of ecosystems such as the rainforests or market mechanisms such as carbon trading, attempts are being made to eliminate such concerns from the texts being proposed.

Loss and damage

At the same time, several prominent developed countries, including the US, Australia, Japan and Canada, have stalled progress on a revamped ‘Loss and Damage’ arrangement to developing countries severely impacted by climate change related hazards.

Advances in climate science now enable attribution of human related causes of extreme weather events to be made in a way that was not possible a few years ago. A quantification of this contribution to individual devastating events such as tropical cyclones or deadly heatwaves is increasingly possible and may in future underpin compensation claims from countries thus affected.

These are countries of course who have not made substantial contributions to the climate change problem and may with some justification seek reparation from those richer countries with historical responsibilities to bear.

There is also a serious risk that the new round of pledges due in 2020 under the Paris Agreement will not have the strict methodology necessary to ensure that they move from aspiration to action.

The ‘woolly’ language which characterised the previous round of pledges (Nationally Determined Contributions) is not going to be eliminated on the basis of what has transpired this week, and countries will probably emerge with a lot of the ‘wriggle room’ they are now negotiating for.

The United Nations Environment Programme recently reported that it would be necessary to cut global emissions by 7.6 per cent every year for the next decade to meet the 1.5°C Paris target.

Self-interest still in abundance

In opening the conference, Secretary General António Guterres warned that climate change was now close to the point of no return. Yet these concerns do not sway the national negotiators away from their focus on national self-interest.

Rather, it is the wording of clauses and procedural issues that occupy their attentions as they seek to avoid concessions that they will have to sell to their superiors on their return.

One would think that as bush fires in Australia approach Sydney, and Victoria Falls runs dry, and after the once in a thousand years summer heatwave has paralysed parts of Europe, some kind of wake-up call would take place.

But countries such as the US, Russia, and Australia have been less than progressive in the negotiations thus far. When Brazil, India, China and Saudi Arabia are added to the mix, the omens for significant progress are not promising.

The EU is also not leading the charge. A new Commission has just been appointed and the ‘New Green Deal’ looks set to call for increased ambition in terms of emission reductions. At COP24 last year the EU Commission was among a group of 27 countries who resolved to step up their ambition by 2020.

Notably, Ireland was not a signatory. Recently, eight Member States wrote to the Commission urging an increase in the EU’s 2030 target from 40 to 55%. The signatories again did not include Ireland and there is currently no transparency on what Irish negotiators have been given as a mandate on this crucial aspect.

Usually, it is possible to detect early in a COP whether countries have come to do business or not. Thus far the positive vibes of Paris in 2015 are not detectable and unless dramatic leadership is displayed now, COP25 is not going to make a dent in the rising curve of global emissions.

By Professor John Sweeney

John is emeritus professor of geography, Maynooth University and has taught and researched various aspects of climate change for over 35 years.