Opinion: Climate Bill pivots Ireland from Tax Haven to Carbon Haven

30 June 2021

Recently, G7 leaders endorsed a global minimum corporation tax rate of 15 per cent, writing Ireland’s industrial policy of the last few decades on the wall.

Though coolly greeted as inadequate in addressing the unsustainable production and consumption practices visited on the global south by aid charities such as Oxfam, the frostiest reception was the Irish state’s, albeit for different reasons.

The reason? An Irish economy built on attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) to Ireland, largely by insulating the profits of multinational corporations from taxation via arrangements such as the Double Irish. A tax haven, in other words.

This forgoing of tax revenue created jobs for the Irish public, with the Irish state offsetting lost corporate taxes with incomes taxes.

While the Irish state has benefited from this model, the jobs now in question are non-unionised, often precarious and low-paid.

For example, half the “employees” of Google are in fact contractors with lower wages and conditions, with many of the permanent employees being hired from overseas due to inadequate investment in Irish ICT skills and education.

In a 2019 NERI report, Precarious work in the Republic of Ireland, the last decade has seen continuous growth in precarious work, with Ireland having among the lowest rates of transition from temporary to permanent contracts in the EU.

The state’s specious claim that the tax haven generates considerable revenue directly on FDI capital is undermined by the relatively minor loss of €2.2 billion to the exchequer portended by the G7’s global minimum corporate tax rate of 15%.

A simple comparison of this figure to the profits of these corporations surfaces an unedifying picture of a middleman economy that facilitates tax evasion for negligible return.

At every point, both historically and since austerity, the Irish state has chosen the shortcut route to “global success” over living up to its basic responsibilities to secure the future of an economy in prevailing and foreseeable circumstances.

The G7 statement signals a ‘Structural Transformation’ in the global economy; a fundamental change in the basic way that an economy or market functions. Faced with such transformation, the Irish State can either resist or adapt. The response is unimaginative cleaving to a failing free rider paradigm.

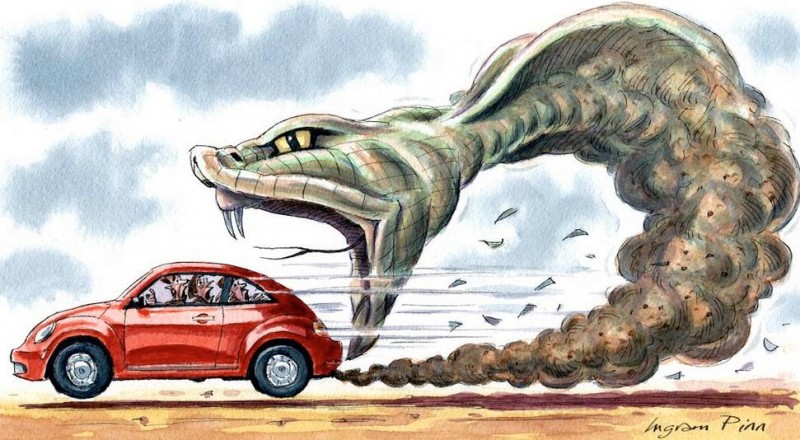

Having operated a deregulatory approach to capital, the State is in serious danger of pivoting to applying this same logic to the climate crisis.

Carbon emissions are moving towards being viewed as a finite resource rather than being an unmeasured and therefore notionally infinite ‘bad’ or negative externality.

We know that the amount of carbon consumed must be reduced otherwise the life-support system we rely on will collapse. The Irish state has not failed to notice this, resulting in the opportunistic logic we apply to the taxation of capital now being applied to carbon emissions.

While the rest of the EU moves away from carbon intensive industry, our state is available to circumvent carbon reduction obligations. Two case studies help illustrate this: data centres and cheese factories.

First, data centres. It was reported in The Sunday Business Post on June 9th that Eirgrid expects 25% of Ireland’s electricity demand to come from data centres by 2030.

It was further reported on June 13th the number of data centres requested would reduce planned carbon emissions reduction from the electricity sector from a target of 60% to 40%.

Planning is already in place for nearly 100 more data centres in this jurisdiction.

Once a data centre is in place, Ireland’s lax regulatory framework makes it immovable. We stare down the barrel of a future that echoes the recent past; where rolling blackouts are justified by future governments in a way similar to California in the early 2000s to protect a pro-market status quo.

But why is the Irish state continuing to encourage the construction of data centres which put our electricity supply and carbon emission goals at jeopardy for minimal employment upside?

It is hard not to conclude that the state believes requirements to reduce carbon on a global scale are a source of arbitrage for attracting FDI from technology companies such as Google, Facebook and Amazon.

The more carbon reduction is long-fingered and watered down, the more time the state has to attract and retain technology companies’ investment through this immobile data centre infrastructure, discounting long-term consequences.

As these data centres cause our energy needs to expand beyond what was planned, there is a strong possibility our natural environment will pay the cost as fossil fuel energy generation is extended and costly mistakes in the renewable sector, such as the Derrybrien wind farm, are repeated.

Recently, we saw the draining of a peatland lake for a wind farm on land proposed for a Mid-Shannon Wilderness Park and a marine planning framework which makes way for economic activity, such as offshore wind farms, but puts marine protected areas (MPA) on the long-finger.

Importantly, the additional burden of carbon reduction planned for the electricity sector was designed to provide headroom for sectors like agribusiness to continue expanding.

This leads to the second example; the government’s aggressive defence of the joint Glanbia and Dutch company, Royal A-Ware plant in Belview. The story of this gouda cheese factory, ostensibly a hedge against Brexit, is actually one of two climate cases.

The Urgenda climate case against the Dutch government resulted in an aggressive climate plan to reduce emissions by at least 25% by 2025. This led directly to a government plan which included restrictions on the Dutch national herd. In this context, the interest of a Dutch agri-food company in a joint cheese manufacturing venture with Glanbia makes a lot of sense. A new Double Irish with cheese.

A pet argument of the Irish agribusiness lobby is ‘carbon leakage’, the idea that if Ireland’s supposed “best in class” farming system does not export meat and milk products then less “environmentally-friendly” countries will fill the gap.

This rather simplistic take on Ricardo’s classical theory of comparative advantage has also recently been taken up by David MacWilliams.

Ironically, this particular cheese factory is in fact an excellent example of one state offshoring its carbon emissions to another. Through EU fines and actions, Irish farmers will end up paying the price while the company will have successfully circumvented climate regulation.

Ireland’s own climate case produced a very different state response: the Irish government has crafted climate legislation designed to frustrate future climate cases.

Dr Andrew Jackson of Climate Case Ireland has pointed out the new Climate Bill reinforces a loophole identified by the High Court, whereby section 15 of the climate act does not apply to the government itself.

The bill also includes explicit language limiting the public’s capacity to sue for the effects of the state’s failure to tackle climate change alongside weak language around climate justice and Just Transition.

Perhaps most damningly, as pointed out in a letter from experts including Professor John Sweeney, the current language on the much vaunted 51% reduction by 2030 is entirely consistent with no reduction, or indeed increases, in emissions between now and 2029.

The only protection against this will be the carbon budgets which the Minister need only adhere to “insofar as practicable”. Defining “practicable” is presumably a task left to the reader. In this case, future governments, the Attorney General or the courts.

These examples and the weakness of the current Climate Bill, suggest, in the same way the Irish State created ‘fiscal space’ to obfuscate the logic of austerity while being a tax haven, it seeks to create a carbon fiscal space for the next decade to better facilitate vested interests in spending carbon; offsetting the cost to the living environments of ordinary people in Ireland and the global south.

We find ourselves at a crossroads. The Irish State can intervene to future-proof our economy if we make the right decisions now.

Alternatively, they can lock in carbon intensive infrastructure that will be impossible to undo, muzzle climate activists by removing legal options from them, water down consistent annual obligations for carbon reductions of at least 7% that would exist in a strong climate bill (such as Scotland’s) and leave pathways for multinationals to undermine an already weak climate bill by accepting CETA’s investor court system that favours the rights of capital over those of the public and the environment.

If this Climate Bill remains as is, a carbon copy of Fine Gael’s climate policies to construct yet more loose regulatory frameworks that protect profit. The Irish government and their credulous accomplices in the mainstream environmental movement will have created the conditions for the next great Irish economic experiment: A pivot from Tax Haven to Carbon Haven.

Lorna Bogue is a Councillor in Cork City South East and a founding member of An Rabharta Glas-Green Left.