Should we put a price on nature?

July 1st, 2016

Last month, a study from the U.S. Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Research Station estimated that trees lining Californian streets provide benefits to municipalities and residents worth $1 billion. They calculated the economic benefits that the trees provided through carbon sequestration, the removal of air pollutants, the interception of rainfall, and energy saving from both heating and cooling. This kind of analysis is becoming more common, but scratching the surface of this seemingly simple idea reveals a fierce debate on whether or not it actually helps the cause of nature conservation. While there are few environmental issues upon which environmental scientists, activists and communicators universally agree, there are none as divisive as the question of whether or not a price should be put on nature as a way of protecting it.

This idea has been around for almost 20 years, since a 1997 analysis by Robert Constanza and colleagues estimated the global value of ecosystem services at $33 trillion/year, a figure that dwarfed Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at the time. The concept that the value of healthy forests, rivers, animals and insects to the global economy could be monetised, and indeed prove crucial to the continuation of economic activity, sparked off a debate that continues to this day.

Putting a price on the economic value of ‘green infrastructure’ (lakes, forests, bogs) and ‘ecosystem services’ (pollinating, producing clean air and water, capturing CO2) is proposed as a means to prevent the destruction of nature, since a financial value can illustrate the clear benefits of leaving nature untouched rather than granting permission to developments that compromise these processes. It could be seen as a way of potentially overcoming the environmental shortcomings of the capitalist economic system, or a ‘market failure’, in which the market prices for environmentally damaging activities, dictated by the laws of supply and demand, do not reflect the full social or environmental costs of such economic activity. For example, take the case of the decline of bees partially due to habitat loss and increased pesticide use. Irish research from Trinity College Dublin found that oil-seed rape would show a 30% reduction in yield without pollinators, valuing pollinators to this crop alone at €4 million a year. If figures like this could be produced in the face of environmental degradation, might they lend some weight to arguments for conserving nature that traditionally would be seen as regressive liberal drivel that stands in the way of “progress”?

Putting a price on the economic value of ‘green infrastructure’ (lakes, forests, bogs) and ‘ecosystem services’ (pollinating, producing clean air and water, capturing CO2) is proposed as a means to prevent the destruction of nature, since a financial value can illustrate the clear benefits of leaving nature untouched rather than granting permission to developments that compromise these processes. It could be seen as a way of potentially overcoming the environmental shortcomings of the capitalist economic system, or a ‘market failure’, in which the market prices for environmentally damaging activities, dictated by the laws of supply and demand, do not reflect the full social or environmental costs of such economic activity. For example, take the case of the decline of bees partially due to habitat loss and increased pesticide use. Irish research from Trinity College Dublin found that oil-seed rape would show a 30% reduction in yield without pollinators, valuing pollinators to this crop alone at €4 million a year. If figures like this could be produced in the face of environmental degradation, might they lend some weight to arguments for conserving nature that traditionally would be seen as regressive liberal drivel that stands in the way of “progress”?

Monetising the value of nature would also help to raise money for conservation projects, which would be very welcome in such a poorly funded sector. Beyond our natural assets becoming self-funding, Tony Juniper, former director of Friends of the Earth England, Wales and Northern Ireland believes that the introduction of this practice could have a profound impact upon economics and society at large. The most outspoken advocate of putting a price on nature within the environmental community suggests that economics would have to change in fundamental ways requiring new government policies, changes to how capital is invested and shifts in consumption patterns. He even warns that campaigning against pricing nature could strengthen the hand of those who believe that nature has no value at all.

Unsurprisingly, the most often cited point on other side of the debate, is the idea that nature should be protected simply because humans do not have any right to treat it otherwise. Writing in Nature in 2006, the marine biologist Douglas McCauley said: “[Conservationists] may believe that the best way to meaningfully engage policy-makers… is to translate the intrinsic value of nature into the language of economics. But this is patently untrue – akin to saying that the civil rights advocates would have been more effective if they provided economic justifications for racial integration.” Proponents of the importance of upholding the intrinsic value of nature maintain that the delight and wonder that we enjoy in nature would be lost by relegating natural processes to the debit column of the accountant’s ledger.

Another common criticism of the proposal is that attempting to calculate the true market value of an ecosystem service will undoubtedly generate an arbitrary figure. You may manage to estimate the amount of flood damage that would be avoided by the strategic planting of native deciduous forestry, but what of the value for mitigating Climate Change through carbon capturing or maintaining the mental health of recreational forest users? Creating a spreadsheet that takes in all the possible economic values and drains of an ecosystem is bound to be an exercise in exasperation. In fact, as pointed out by Guardian columnist George Monbiot, the largest-scale example of attempting to internalise the environmental cost of economic activity, the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), which set a price per tonne of carbon emitted by high-polluting bodies such as power stations and large industrial plants, has arguably not succeeded in bringing emissions down due to the failure to establish an effective carbon price.

A related fear in the same vein of making natural processes tradeable is that it may open various ecosystem services up to being traded separately. The risk of doing this comes from the fact that natural systems are holistic systems which cannot be broken down into component parts without sacrificing overall function. Similarly, as has been discussed in the UK, the idea of ‘biodiversity offsets’ could see invaluable ancient woodland sacrificed to development with biodiversity-poor tree nurseries planted elsewhere to replace them, based on a simplistic economic evaluation of the woodland that is blind to habitat loss or the recreational value of that place to local residents. Does compensation on the loss of a municipal green space make it easier to swallow its disappearance?

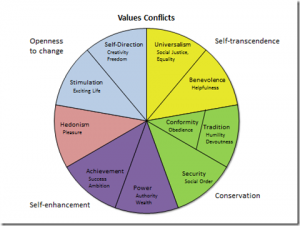

Values on opposite sides of the wheel suppress one another and people tend to be dominant in values on one side of the wheel.

While the above criticisms cover the practical challenges and dangers of placing natural systems on the market, a concern proposed by the psychological research community may represent the most subversive and wide-reaching risk of the scheme. Researchers in the area of human values predict that ascribing a monetary or extrinsic value to nature would erode our ability to appreciate the intrinsic value, not just of nature, but of other concepts such as relationships, community and equality. Seminal research by Shalom Schwartz on patterns of human values in over 70 countries found that they are clustered in very consistent ways across cultures. Self-enhancing values relating to wealth or success, known as extrinsic values, tend to suppress self-transcending values, which consist of concepts such as being helpful and social justice, and likewise the presence of these intrinsic values tend to mean low expression of extrinsic values. Applied to the context of environmental behaviours, researcher Gregory Maio from Cardiff found that including appeals to money-saving in information about car-sharing reduced people’s likelihood to recycle. Since values are acquired through the culture in which we are surrounded, the argument is that the more media coverage and campaigns that reinforce our need for extrinsic motivation to take action, the less likely it becomes that we will step up and do something simply because it is the right thing to do.

This debate is a complex one, and there is not much prospect of a clear winner emerging any time soon. If putting a price on the environment prevents it from being degraded at the current rate, can it really be a bad thing? On the other hand, if we contribute to building a society that only acts on extrinsic values and with self-interest, where will the incentives for good behaviour stop? One thing is clear, however, according to Tony Juniper: “it is not most environmentalists who have misunderstood the realities that come with infinite ‘growth’ on a finite Earth, but most economists”.

[x_author title=”About the Author”]