Opinion: Time to rethink forestry model in response to climate crisis

June 6th, 2019

Forestry is poised to become a critical part of Ireland’s response to the climate crisis. The simple mantra goes ‘Trees are good’ and so planting more trees is a great idea.

However, like everything in life, the truth is a little more nuanced than that. Trees do not grow in isolation. They form part of an elaborate ecosystem.

Above the ground, the insects and birds and small woodland mammals of a forest are easily observable. Below the ground, intricate networks of roots, invertebrates and fungi are critical for supporting the trees growing above.

Over thousands of years all the different organisms have adapted to each other to form what we call a functioning ecosystem. In the case of such a habitat being dominated by trees we call it a forest.

These forests by their very nature are biodiverse supporting a myriad of different species. They also, very usefully, take carbon out of the air and lock it away in the wood, insects, roots and soils of the forest.

Ireland’s forest cover had gone so low, (only Malta is lower) that it was decided we needed state intervention. A forestry company was established and a forestry program was rolled out, in order to get more trees in the ground across the country.

The Irish Forestry strategy has not been to create biodiverse forests of native species of broadleaves, however.

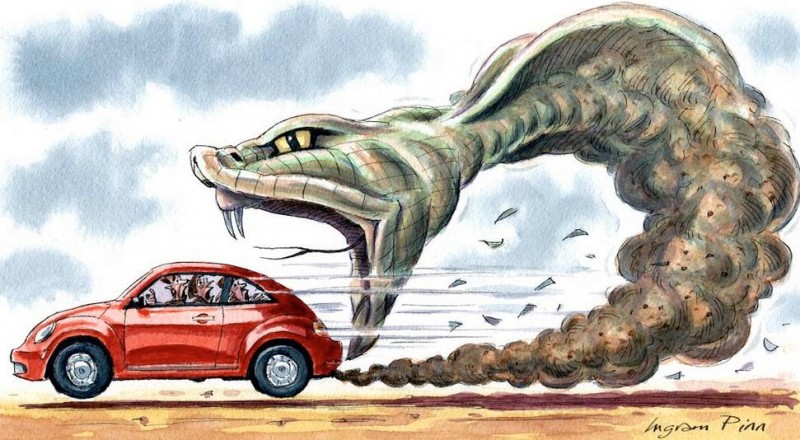

Instead it was decided to create vast industrial plantations of non-native conifers, creating large dark areas of evergreen “Christmas Trees” that we see covering the fields and hillsides of much of our landscape.

Because they are not native, they do not support the wide range of insects, birds and fungi that thrive in native Irish forests. Above the ground they appear as silent dark blocks of spikey green. Below the ground the essential fungi for native trees begin to die off.

They grow quickly, producing poor quality timber, and are designed to be one day cut down en masse, a process called clearfelling.

It is all too common to see the scars left behind by large swathes of land clear-felled in this manner, leaving large ruts in the soil, and upturned tree stumps.

One day a dark tower of conifers, the next a denuded landscape that appears shocking at first site, almost post-apocalyptic.

It is now recognized that this was never the right approach. Policies now demand a 15 per cent area of biodiversity in these plantations. Interestingly, if they were actual forests they would, by definition, be 100 per cent biodiverse.

Increased focus now on the need for forests as a tool for combatting climate change means that we must address the historical mistakes. It will be disastrous to perpetuate them.

The endless rows of closely planted non-native conifers, the industrial plantations, don’t pass the test for being defined as forests.

They don’t support native species, neither above nor below the ground. They don’t even lock away carbon the same way native forests do.

Worse still, if they are planted on peaty soils of which we have plenty in Ireland, they actually can release more carbon than they store.

On all levels they fail to deliver.

Socially, they block light, look out of place on our amazing landscapes, and fail to provide a pleasant walking environment.

Environmentally they are dead zones compared to a native forest. They don’t support native species, and they don’t do an effective job of locking away carbon.

And even in terms of economics, the financial returns from public money invested in forestry are paltry. The state owned Coillte has returned a mere €40 million euro to its shareholders (the Government) since its establishment 30 years ago – not taking into account around €150 million dished out in grants and support.

Is this a good economic return for owning 7 per cent of our landmass?

As we examine the role of forestry in addressing climate change we need to have a serious re-think. It’s time to draw a line under the practices of the past that, no matter how well intentioned, have failed to deliver.

The industrial plantations will not be of use to us in facing our climate targets. In sharp contrast to this, mixed forests of native broadleaf trees are designed by nature, to work with nature.

The forestry industry is well placed to deliver on a restructuring of the plantations, reforming our wooded landscapes. Strong support is needed to ensure we get the right trees in the right place.

Jobs in tree nurseries can be secured by creating a market for locally collected seeds of native trees. This working with nature approach takes advantage of the fact that seeds collected locally produce stronger, faster growing, and better quality trees.

The time is right to change the model. It’s not too late. We still have one of the lowest areas of trees in Europe. We have the best practice models from all other member states. Incentives need to force a restructuring of what we have, and the establishment of new native forests.

These native forests can deliver on all fronts, social, environmental and economically. Forestry is poised to play a critical role in combating climate change.

Let’s not make the mistake of thinking that industrial plantations can do the same.

By Cillian Lohan

Cillian is the CEO of Green Economy Foundation that works in the policy areas of the green economy, sustainable agriculture, educational and biodiversity activities.