The Climate Action Bill recently became law. Now what?

4 August 2021

Climate campaigners have worked for years in Ireland to see this kind of legislation enacted. Once proposed by the Government, the Bill went through months of campaigning, debating, and amendment-adding.

Now that the Climate Action Bill was signed into law just two weeks ago, what do we need to know about it? And what happens now?

We read, called experts, and dug into the legislation to get into the nitty-gritty of it all.

First things first – what do I need to know about the Bill?

In a nutshell, the Bill to is intended to approve plans that pursue ‘the transition to a climate resilient, biodiversity rich and climate neutral economy’ by 2050.

Some key elements of it include putting targets into law through carbon budgets and the establishment of both a Climate Change Advisory Council and Climate Action Plan. That plan is expected to be released this autumn, and the targets will be held accountable by sector and local authorities.

What’s really important to keep in mind here is that this legislation doesn’t include the specifics. According to Friends of the Earth Ireland Director Oisín Coghlan, it sets the rules of the game and but can’t determine the outcome.

In other words, this Act determines how to make the climate policy, check that policy and ensure that it’s being implemented. It’s not detailing the specific actions that will be undertaken.

So while activists will still have to campaign for policies, there are now legal targets the government must meet. Now “there’s a process that is more transparent, more evidence-based and more accountable than ever before,” Mr. Coghlan told The Green News.

These legal targets are known as carbon budgets. The first two of these budgets must reduce emissions by 51 per cent from 2018 levels by 2030.

(Side note: you might remember that back in April a number of experts voiced their concern over language in the Bill around a 51 per cent emissions reduction by the end of the decade. Check that piece out for the full explanation.)

Okay, so carbon budgets are a key component of this Bill. But I’m still a little unsure of what a carbon budget actually is.

To start, it has nothing to do with money. The reason why it is called a budget, is because generally we already have an understanding of what a budget is.

“When we budget for money, we only have this much money and this is how to spend it,” Mr. Coghlan said. “So the point of a carbon budget is we can only burn this much carbon.”

As it is set out in the Bill, the carbon budget, “will be a number that covers a five-year period and the total amount of greenhouse gas emissions that Ireland is allowing itself to emit,” according to MaREI Director Professor Brian O Gallachoir.

Initially, three numbers will be proposed by the Climate Change Advisory Council. These will represent the budgeted amount for the 2021-2025, 2025-2030 and 2030-2035 periods. Though only the targets for the next 10 years will be adopted by the Oireachtas.

The way it’s set up, “the council always give us 15 years’ worth of five-year targets and the parliament will always adopt 10 years’ worth of targets” in Mr. Coghlan’s own words.

Though determining these numbers is complicated.

“While it sounds simple to produce three numbers for three, five-year carbon budgets, it’s complex,” said Prof O Gallachoir.

The numbers must be weighed against several considerations including climate science, the EU policy perspective, the Paris agreement, and implications for the economy and jobs.

How important is the first budget and what should we look for?

The first carbon budget is “critically important” according to Prof O Gallachoir. This budget sets out a clear short-term ambition and is a driver of action.

“The carbon budgets are very clear, enshrining of the collective targets that we’re all aiming for,” Prof O Gallachoir explained. “The failure to meet the first carbon budgets, would be very damaging.”

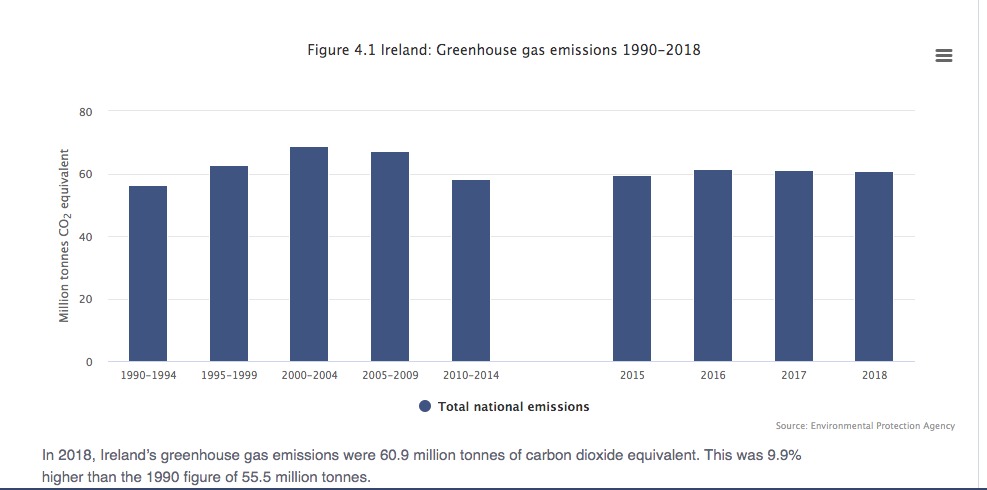

Currently, Ireland emits roughly 60 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent each year. So a carbon budget that would be at a ‘stand still’ would allow for 300 million tonnes of CO2 to be emitted.

Coghlan would like to see a carbon budget of 250 million tonnes for the first five years and 175 million tonnes for the following five years. So that would be 425 million tonnes for the next ten years. Though Coghlan admits, “that’s probably optimistic.”

The Bill doesn’t set incremental targets, so there is a potential for emissions reductions to be back-logged. Otherwise, each year might see an annual reduction target of 7 per cent.

But emissions reductions won’t be seen evenly each year. This is in-part because it takes time to implement emission-reductions. Simply put, public transport, retrofitted houses and wind turbines can’t be built overnight.

So careful planning and implantation are necessary to see these targets through. As Mr. Coghlan says, “you can’t expect to halve emissions in five years. It just isn’t physically possible.”

So we can expect carbon budgets to determine emissions – but how will sectors be held accountable?

This is what has “changed the whole dynamic”, according to Oisin Coghlan.

Now, once the carbon budgets are implemented, each sector negotiates for their “slice of the pollution pie”.

“Emissions reductions are easier to achieve in some sectors compared with others,” Prof O Gallachoir explained, who also noted that “emission reductions have different impacts in the different sectors.”

This understanding this is key to establish the expectations of each sector in the carbon budget.

For example, agriculture contributes more than any other sector, with 33 per cent of overall emissions. A current roadmap for the sector suggests this sector might reduce their emissions by 10 per cent by 2030.

But if that’s all they do, the rest of the economy will “have to reduce emissions, pretty much by three quarters to meet the overall target of 51 per cent”, Mr. Coghlan said.

Hannah Daly and Paul Deane highlighted this in a piece for the Sunday Business Post, who also found that “in effect, it would require a much higher level of effort in the sectors outside of agriculture to compensate.”

It’s thus crucial that “every sector does its fair share,” he added. Rather than a presumption that a sector may do less than the average, it would need to justify why less action should be taken.

But what happens if the targets are not met?

It would set off a “hamster wheel of embarrassment”, joked Mr. Coghlan.

While the targets are binding, it’s just “parliamentary accountability” and “political embarrassment” that keep the minister and government in check, he said.

Well, that and the looming possibility to end up in court in targets are not met.

Lastly, what’s next? What are we looking forward to seeing with this Bill?

Though this has been repeatedly lauded as landmark legislation, that doesn’t mean the work is over.

“We set ourselves a high ambition, we’ve legally enshrined it. And now, the next steps will determine how that ambition is translated into action,” explained Prof O Gallachoir.

In the upcoming months we will begin to see the detail that emerges from this broad legislation.

“But policies by themselves don’t deliver the action,” reminded Prof O Gallachoir. He argues that there is a need for both evidence-based policy, but also societal buy-in.

So, after this “significant change” in the political landscape, Prof O Gallachoir thinks “it’s important to acknowledge and celebrate that. But not to take our eye off the ball, which is to translate that now into action.”

Coghlan echoed that sentiment, “if we delay action any longer, we aren’t doing our fair share.”

By Sam Starkey