Coronavirus puts degrowth on new, rapid trajectory

March 24th, 2020

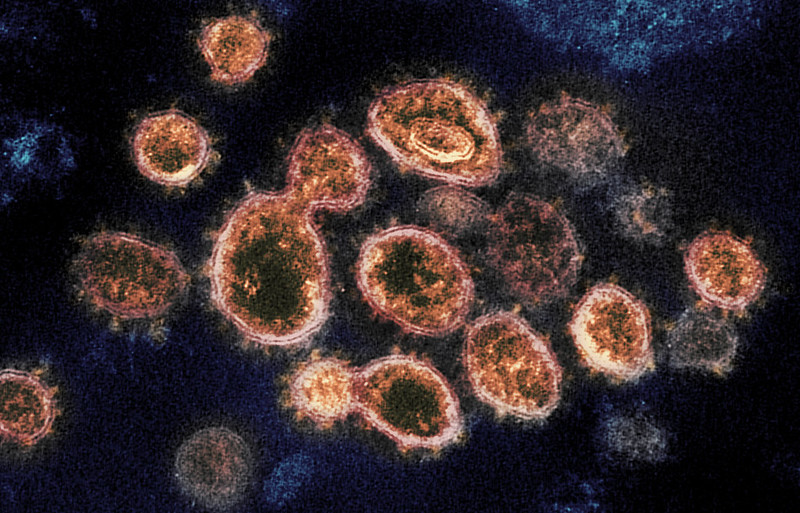

SARS-Cov-2 has put the idea of degrowth in a new perspective and on a necessarily more rapid time scale. Up to this point, those writing about degrowth envisioned a contraction of economic activity over years or decades. But now the global pandemic is requiring action in days, weeks and months.

The steps to quarantine, self-isolation or social distancing in order to suppress a dangerous virus pandemic is a public health motivated strategy and it inevitably brings economic degrowth with it.

But degrowth has never been solely about economic contraction. It is also about changing the current economic structure into something better. But we don’t get to choose the conditions in which degrowth will play out right now. We are being forced to change to stay alive.

The virus means staying at home – and thus not using fossil fuel powered transport (including public transport and planes). It means minimal shopping – only for essentials. It means not going to restaurants or on holidays.

It means the temporary closure of many production processes, a reduction in the transport of many goods and a large proportion of world trade. Some of these production processes, trade and transport will never re-start and the associated economic organisations are likely to go bust.

Essential and inessential production

Where such production is inessential and only exists to allow rich people in an incredibly unequal world to preen and celebrate themselves, this is no bad thing. The economy has overshot the carrying capacity of the biosphere and this reduction is what is needed.

However, when this is all over, will inessential and ecologically toxic activities restart? Some might but I doubt it for most of them – this kind of historical process is not reversible. When businesses are liquidated one cannot just start them up again – unless there is a real need.

The death and suffering brought about by the coronavirus, the frosted glass in the lungs, of vulnerable people is a tragedy. The inability to buy Gucci and other luxury fashion lines together with a demand shock for luxury goods is not. It is to be welcomed.

What is true is that the workers in this sector will be worried about their jobs, paying their debts and their future – I do not wish to make light of their fear and distress. But from the point of view of the environment and public health it is good if people start looking for a change in direction in life and it is important that they are encouraged to do so.

It is not possible to degrow the economy without a lot of people having to change their jobs and retrain. At the right time they should be helped through the stress and financial turmoil. But these are changes that have to happen.

When supporting people in fundamental occupational changes, the jobs that they should be encouraged to retrain for should be in fields where ecology and economy are not in conflict.

Food production in the growth economy

Above all, it is the food sector that needs to change most as this is where health risks largely originate. We will need a massive transformation in sectors like food growing, food processing and marketing focused on sites local to farmers.

Much of the case for re-localisation and degrowth is motivated by the greenhouse gases arising in transport and farming. However, what this crisis is also trying to teach us are frightening truths about the ecological consequences of land use changes that have emerged as threats to our health.

If we are to slow down the rise of new diseases like COVID-19, then we need to acknowledge that they are emerging from the ways that industrial, agricultural and urban expansion have brought about land use changes that are disrupting ecological systems.

Pathogens previously boxed into niches of ecological systems are now interacting with monocultural farming systems and human food chains. Bats are not just associated with COVID-19 but also Ebola and it is the ecological disruption when forests are displaced by plantations that have brought bats into closer contact with humans.

And that’s not all. The real estate markets of cities are extending suburbia into the surrounding countryside. This has consequences too – increased Lyme disease spread by ticks and hosted by mice for which suburbia is an ideal habitat.

Climate change and economic development have changed weather patterns and wild animals – insects, birds, mammals – have been forced to adapt, bringing about new kinds of interaction with humans in which we get infected by “novel” diseases.

Meanwhile, the Industrial farming of animals – the mass production of meat – has entailed fundamentally unhealthy (and thus cruel) ways of raising and treating animals. To prevent them from getting sick, antibiotics are routinely used to the point that they are losing their effectiveness as a medicine for humans.

Ideal of degrowth superseded by real life events

Self-isolation and distancing is the beginning. It will bring the economy down and is already doing so. Normally, it is other people and other species that carry the so called external costs of economic development while corporate magnates reap the profits.

This time round a virus is unleashed that destroys the very foundations of economic activity and the corporations too. Up to this point, economists and central bankers could ignore the ecological crisis but now they find that the ecological disruption is unleashing a Pandora’s Pox of problems for which they have no answer.

In the long run, policies of social isolation and quarantine will hopefully prevent a lot of people from dying before they need to. But these temporary expedients are pulling the global economy down. In the demolition site we will have to start again with something different. That’s so we do not just go back to the same place this catastrophe started from.

If the process is badly managed and the production of essentials goods and services collapse altogether then a lot of people will die anyway. Managing this process both at the policy level and at the personal level will be not be easy to judge. People will have to work together to produce food – how much they will need to come together to frequent restaurants and pubs is another matter.

How this is to be done is something that all of us individually and as households will have to work out as we go along. It is a time for improvising and making careful and distanced arrangements with neighbours.

The new normal

Human and natural systems evolve in three dimensions – productive capacity; inter-connectedness; and the degree of resilience or vulnerability. In recent years the economy, society and ecological system has become more vulnerable to domino chains of cascading collapse.

Over more than two centuries the high level of complexity and connectivity in the economy has increased productive capacity. However the high level of connectivity – where products are assembled from components from supply chains spanning the globe – is very vulnerable and has been collapsing.

The finance system is another highly connected system that is very vulnerable which can collapse in a situation like the coronavirus crisis. This throws people back, in extremis, to the resources of their own household and its immediate environment.

Social support mechanisms and economic relationships will be under pressure to minimalise. To take a trivial example – we can still take deliveries at home which can be left outside the door for collection (inclusive of arrangements for disinfection).

There will be no one size fits all ways of doing

it and each person will have to improvise during this crisis. At the same time

the ideal outcome is that improvisations will lead to fundamental changes that

start the re-localisation of economic activity, changes in the food system and

land use – and in general degrowth.

Forget about a return to normal – the normal was unsustainable and this is the

result.

By Brian Davey

Brian is an ecological economist and has spent most of his life in the community and voluntary sector in the areas of health promotion, mental health and environment. He is a member of Feasta’s Climate Working Group and author of Credo: Economic Beliefs in a World in Crisis. This article is abridged from a piece on the Feasta blog here.