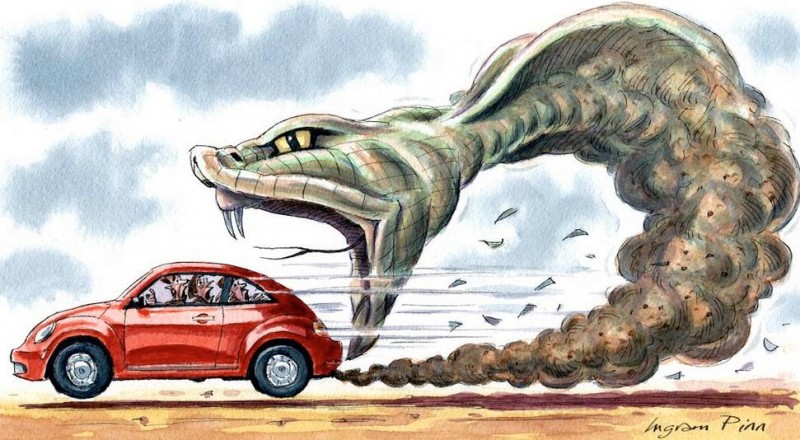

Missed opportunity for societal dialogue on climate crisis

December 3rd, 2019

Last Wednesday, the Department of Climate Action and the Environment (DCCAE) launched a public consultation on Ireland’s long-term strategy to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, containing 26 questions ranging across all sectors and covering the period to 2050.

The timing and original length of the consultation, however, represents a missed opportunity for a meaningful societal dialogue on the climate crisis and Ireland’s response.

Under the EU Regulation on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action, each member state is required to submit a Long-Term Strategy for GHG Reduction to the European Commission by 1 January 2020.

The regulations require that “the public is given early and effective opportunities to participate in the preparation” of the strategy. As such, these requirements can’t have come as a surprise to the Government.

The detail of the regulation was signed off by the EU Council and European Parliament in June 2018, and it entered into force on 24 December 2018. Yet, despite having notice of roughly a year and a half of this requirement, DCCAE left it until almost the last moment to conduct a public consultation on the strategy.

Launched on 26 November 2019, the consultation was initially due to close on 16 December, a period of just 15 working days. This would have given civil servants in DCCAE just nine working days to review and incorporate feedback received from the public before the 1 January deadline, assuming they would take no leave over the festive period apart from public holidays.

Extended consultation deadline

The Department subsequently extended the deadline to 31 December, giving an extra 10 working days for interested parties to make their submissions. It remains unclear when DCCAE intends to submit the finalised strategy to the European Commission.

Although the extended deadline is welcome, the conduct of the consultation is arguably still in breach of the Government’s own guidelines on public consultations. These guidelines recommend consultations last for between two and 12 weeks, but they specify that “where stakeholders are being asked to consider the whole proposal and there has been little previous consultation, a longer consultation period is appropriate”.

The guidelines also indicate that “longer consultation periods may be necessary when the consultation process falls around holiday periods”, as in this case.

In its defense, the Department has been massively stretched over the past year. Its tasks have included elaborating and finalising Ireland’s first National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) for the period of 2021 out to 2030 which must also be also submitted to the EU by 1 January 2020.

In addition, it worked hard to formulate the all-of-government Climate Action Plan that was published in June, and staffing and resource levels across the civil and public service have not yet caught up with the increasing demands of the state’s new-found focus on climate change.

DCCAE also defended its approach by pointing to the public consultations it ran in the preparation of Ireland’s first National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) covering the period 2021-2030. While the NECP public consultations were much more satisfactory, they are an inadequate substitute for robust public consultation on the long-term strategy.

A missed opportunity

The long-term strategy consultation represents a missed opportunity to launch a meaningful societal dialogue on Ireland’s economic and social future in the context of responding to the climate crisis.

There are at least three reasons why such a dialogue could be helpful.

First, policy debates often get caught up in the detail of immediate choices and trade-offs. A discussion on Ireland’s long term climate policy direction could have provided an opportunity for a more valuable and productive society-wide debate.

Second, some of the more profound policy choices on the path to a low carbon future require a time horizon of longer than a decade. Limiting our vision to 2030 arguably makes it harder to identify some of the more transformational changes we need to make, particularly around spatial planning and large infrastructure investment.

Third, the Climate Action Plan and the NECP – both with a 2030 horizon – should have been informed by a clear vision of where we want to be 30 years from now. Only by collectively deciding on our desired destination can we develop a coherent map of how to get there.

With sufficient time and resources, the National Dialogue on Climate Action could have provided a mechanism for innovative public engagement to feed into preparation of the long-term strategy. In addition, a truly deliberative national climate stakeholder forum could have provided a venue for meaningful input by societal groups.

It may be too late for a meaningful process of societal and stakeholder engagement to feed into preparation of our long-term strategy, but it is not too late to start such a conversation. It is urgently needed.

By Dr Diarmuid Torney

Diarmuid is an Associate Professor in the School of Law and Government at Dublin City University. He teaches on DCU’s MSc in Climate Change: Policy, Media and Society.