New study shows traffic air pollution stalls children’s brain development

August 3rd, 2017

Traffic-related air pollution in cities can hinder the brain development of children, according to a Spanish study of over 2,500 school children.

The study, which is part of the EU-funded BREATHE project, found that higher concentrations of traffic-related airborne pollutants reaching classrooms negatively impacted children’s performance.

Of the 2,687 students that were involved in the study, those exposed to the highest concentrations of pollutants performed the worst in standard computer tests.

Particles in the classroom

The study measured the concentrations of ultrafine (less than 2.5 micrometres) particulate matter (PM2.5) in 39 schools at different distances from major roads across Barcelona.

The results showed that schools closest to major roads had the highest concentrations of pollutants in their classrooms.

“If you move traffic 50 metres from a school, ultrafine particle amounts drop by more than half,” said Professor Jordi Sunyer of Centre for Research in Environmental Epidemiology, who led the study.

“At 200 metres, you get 10 times less,” he added.

In addition to computer tests of attention capacity, the team also used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to show that the development of a region of the brain associated with decision-making, social behaviour and complex thinking was impaired.

Among the other findings, Sunyer and co-authors found that a child’s test performance could be negatively impacted on test days after high pollution days.

They also showed that students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) were particularly susceptible.

Based on the evidence gathered, Prof Sunyer advocated that schools should not be built within 50 metres of a road and that pollution barriers such as hedges and trees should be put in place.

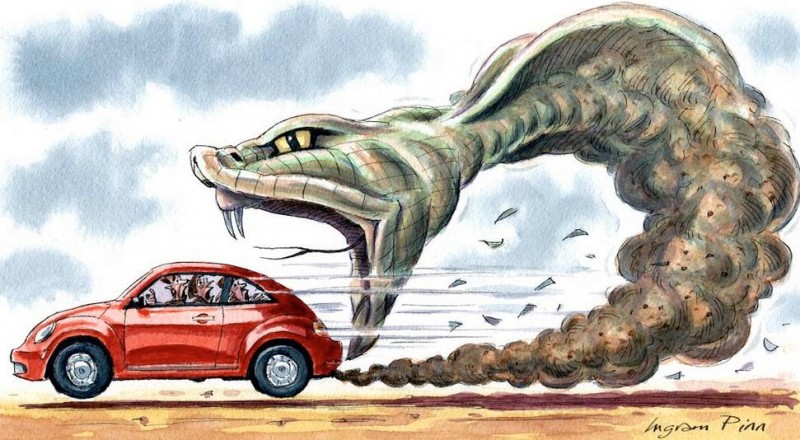

Diesel engine exhaust a major concern

The research is the latest in a series of studies highlighting the negative health impacts from air pollution.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), about 7 million deaths are caused by air pollution each year and of all pollutants, particulate matter impacts the most people.

Research has increasingly linked negative health outcomes to the growth of diesel car ownership over the past 10 to 15 years.

The trend toward purchasing diesel cars was a consumer response to measures adopted in many countries to increase the number of cars with lower carbon emissions on roads.

This translated to consumers buying diesel cars over petrol alternatives. In Ireland, diesel car sales went from about 30 per cent in 2007 to near 70 per cent in 2015.

Yet, despite emitting less CO2 per kilometer, diesel engines emit significantly more particulates and nitrogen oxides (NOx) than petrol cars.

Scientists and environmental campaigners have continually warned of the dangers of urban diesel exhaust emissions and have called for measures to be taken to move away from diesel.

In recognition of these health hazards, most EU countries are moving to implement measures to reduce the number of diesel cars on roads.

[x_author title=”About the Author”]